Par-delà les scissures et les sillons

William H. Calvin

William H. Calvin est

neurophysiologiste à l’université de Washington à Seattle, Etats-Unis.

Son prochain ouvrage, écrit avec le linguiste Derek Bickerton, s’intitule :

Lingua ex Machina : Reconciling Darwin and Chomsky with the Human

Brain (MIT Press, 2000)

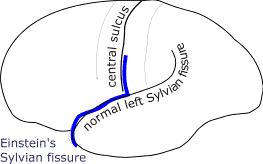

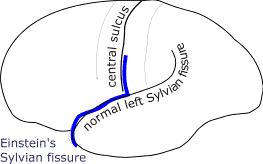

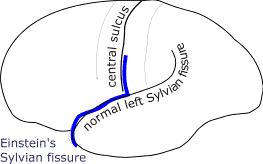

Placez la photographie du cerveau

d’Einstein au milieu d’une centaine d’autres clichés du même type :

il ne fait aucun doute que n’importe quel étudiant en neurosciences le

repérerait immédiatement. “ C’est aussi étrange que d’avoir

deux pieds gauches, dirait-il. Comment cet individu pouvait-il danser

avec deux cerveaux droits ? S’agissait-il d’un attardé mental ou

d’un génie ? ” Les règles de l’origami prénatal nous

sont encore largement inconnues, mais chaque étudiant apprend vite à

distinguer les replis les plus profonds du cerveau, tels le sillon central

(tout ce qui est situé en avant de ce sillon est appelé le “ lobe

frontal ”) et la scissure de Sylvius (tout ce qui est situé en

dessous de cette scissure est appelé le “ lobe temporal ”).

Habituellement, les deux hémisphères n’ont pas la même apparence :

dans un cerveau droit typique, la scissure de Sylvius prend un tournant

abrupt, un peu en arrière du sillon central, tandis que, dans le cerveau

gauche, sa courbure est beaucoup moins prononcée (voir l’article

d’Olivier Robain). Il sauterait donc aux yeux de notre étudiant que ces

pliures dans les cerveaux droit et gauche d’Einstein sont curieusement

similaires. Autre bizarrerie, les coudes des scissures de Sylvius sont situés

plus en avant qu’à l’ordinaire : chez Einstein, toutes les deux

aboutissent dans le sillon central.

Les frontières des nations suivent souvent

les vallées ou les lignes de crêtes, mais pas toujours. La règle et ses

exceptions valent aussi pour les frontières fonctionnelles du cerveau.

D’ordinaire, par exemple, la crête située en arrière de la vallée du

sillon central traite les informations liées aux sensations de la peau (la

“ bande sensorielle ”), tandis que la crête située en avant

de ce sillon est associée aux muscles. Les traitements des sensations et

des mouvements semblent ainsi séparés par une vallée profonde, mais les

neurochirurgiens sont fréquemment confrontés à des exceptions : par

exemple, tel ou tel patient éveillé leur fera part de sensations alors que

des électrodes stimulaient son lobe frontal. Au sein de la bande

sensorielle, l’aire située en arrière de la partie associée au visage

et aux doigts a la réputation d’être essentielle pour la capacité à se

situer dans l’espace, par exemple retrouver sa voiture dans un parking.

Chez Einstein, cette aire semble être 15 % plus large que la moyenne.

Y a-t-il une conclusion intéressante à

tirer de cette anomalie ? Pas vraiment. Tout au plus peut-on affirmer

qu’il serait judicieux d’examiner des cerveaux vivants à l’aide des

moyens modernes d’imagerie cérébrale : en cherchant des exemples de

plis rencontrés chez Einstein, on pourrait ainsi examiner comment les

individus concernés se comportent vis-à-vis des fonctions que nous pouvons

mesurer, par exemple l’intelligence, la créativité, les capacités

verbales et spatiales.

À la suite de la phrénologie de Gall,

nous avons toujours tendance à faire comme si une aire était exclusivement

dédiée à une fonction. C’est peut-être vrai pour le cortex visuel,

mais la plupart des aires sont multifonctionnelles, à la manière de

certains aménagements de nos trottoirs : conçus pour faciliter le déplacement

des fauteuils roulants, ils sont mis à profit aussi bien par les vélos que

par les chariots de supermarché ou les valises à roulettes. La pratique de

nommer une aire cérébrale d’après la fonction qui a permis de

l’identifier conduit à une réification fallacieuse : ça porte un

nom, donc ça doit être une chose, donc il doit y avoir d’autres choses

dans d’autres endroits !

Un expert contemplant le cerveau

d’Einstein évitera de commettre cette erreur de débutant, mais il ne

saura guère faire mieux qu’un étudiant pour expliquer ce que signifient

ces plis peu ordinaires. Nous savons tous trop bien que, d’un cerveau à

l’autre, il existe des différences aussi importantes qu’entre deux

visages. Cependant, nos connaissances demeurent très limitées quant aux

conséquences de ces variations sur l’amélioration ou la diminution de

certaines capacités. Par exemple, le cortex visuel à l’arrière du

cerveau est trois fois plus grand chez certaines personnes que d’autres.

Celles-ci ont-elles une meilleure acuité visuelle ? Savent-elles mieux

discriminer les couleurs ? Pour l’instant, personne ne peut le dire.

S’il semble exister une faible corrélation

entre quotient intellectuel et taille du cerveau, il y a des génies aux

deux extrémités du spectre (en l’occurrence, le cerveau d’Einstein est

10 % inférieur à la moyenne masculine, même après correction sur

l’âge). Est-il véritablement pertinent de porter notre attention sur des

cerveaux de taille importante ou, plus fréquemment, sur des régions

anormalement développées de cerveaux normaux ? Nous nous intéressons

à la taille parce qu’elle est facile à mesurer, mais ce que nous

voudrions réellement savoir, c’est le degré d’agilité, de créativité

dont fait preuve un cerveau. D’Einstein, on peut penser que le calcul ou

la déduction n’étaient pas ses préoccupations majeures, qu’il

s’agissait avant tout pour lui d’imaginer une explication du

fonctionnement de certaines parties du monde physique, puis de rechercher le

meilleur accord entre cette explication et le monde réel. Mais

qu’entendons-nous plus précisément lorsque nous employons le mot “ intelligence ” ?

Si l’on suit Jean Piaget,

l’intelligence est surtout ce qu’on utilise quand on ne sait pas comment

agir, quand ni l’inné ni l’apprentissage ne nous ont préparé à une

situation donnée. Trop souvent, le terme désigne à la fois un vaste

ensemble de capacités et l’efficacité avec laquelle elles sont mises en

œuvre. Cependant, l’intelligence implique aussi flexibilité et créativité,

une “ capacité à échapper aux liens de l’instinct et à

engendrer de nouvelles solutions aux problèmes posés ”. En résumé,

l’intelligence relève de l’improvisation.

De la même façon qu’une maison n’est

pas seulement un tas de matériaux de construction, c’est la structure de

la pensée qui rend les capacités mentales d’un humain très différentes

de celles d’un singe. Nos conceptions modernes de l’intelligence n’ont

guère accordé d’intérêt à la question du choix du bon niveau, ni trop

prosaïque, ni trop abstrait, qui est nécessaire pour la résolution d’un

problème. Qu’est-ce qu’un niveau ? Regardons la façon dont les bébés

découvrent le monde qui les entoure. D’abord, ils repèrent les motifs

sonores du discours (les phonèmes), puis les motifs qui forment des mots,

puis les motifs entre les suites de mots que nous appelons la syntaxe, enfin

les motifs faits de longues suites de phrases que nous appelons des

narrations. Voilà une pyramide de niveaux ! Plus tard, lorsque

l’enfant aura grandi et qu’il s’attaquera par exemple à l’Ulysse de

James Joyce, on sait qu’il devra être capable d’aborder plusieurs

niveaux à la fois. Que ce soit dans la lecture de Joyce ou l’interprétation

des conversations courantes, une grande partie de notre activité

intellectuelle consiste en fait à localiser les niveaux appropriés de

signification. Pour passer du temps dans les niveaux plus abstraits d’un

château de cartes intellectuel, les premiers doivent être suffisamment

consolidés pour éviter l’effondrement de l’ensemble. Einstein était

probablement bon dans cet exercice. Les poètes aussi, mais Einstein devait

en permanence entretenir une relation pertinente entre les niveaux les plus

abstraits et les plus concrets. Une symphonie était à l’œuvre dans ce

cerveau bizarrement plissé, engendrant une superbe cohérence avec ce qui

se passe dans le reste de l’univers.

W. H. C.

Pour en savoir plus :

J.P. Changeux, L’homme neuronal,

Fayard, 1983

M. Turner, The Literary Mind, Oxford

University Press, 1996

D.C. Dennett, La diversité des esprits,

Hachette, 1998

W.H. Calvin, G. A. Ojemann, Conversations

with Neil’s Brain, Addison-Wesley, 1994

W.H. Calvin, The Cerbebral Code, MIT

Press, 1996

A.R. Damasio, The Feeling of What

Happens, Harcourt Brace, 1999

in the original English (was shortened considerably)

Contemplating Einstein's Brain

William H. Calvin

There's no doubt that Einstein's brain is exceptional in appearance. Even

if photographs of it were to be placed anonymously in a rogue's gallery of a

hundred other brain photos and given to a beginning neuroscience graduate

student to sort somehow, it would be flagged as odd. "Talk about two left

feet," she would say, "I wonder how this guy danced with two right

brains? And was he mentally retarded, or a genius?"

Einstein's left brain looks something like the mirror image of a right

brain, if you're judging only from how the sheetlike brain surface has been

folded up. We don't really understand the prenatal origami yet, but everyone

soon learns to spot the deepest folds, such as the central sulcus (we call

everything in front of it the "frontal lobe") and the Sylvian

fissure (everything below it is the "temporal lobe," looking

something like the thumb on a boxing glove).

Usually, the two brain halves are not quite the same in appearance, thanks

to how the Sylvian fissure takes a dog- leg turn upward in the typical right

brain, a bit in back of the central sulcus, whereas the left brain's Sylvian

usually takes a gradual rearward course. What that student would have noticed

is that Einstein's left brain looks like a right brain folding pattern

(actually, it's an exaggerated version, with the dog-leg turn even farther

forward than usual; indeed, in Einstein, both the left and right Sylvians turn

up into the central sulcus). Such paired dog-leg turns are unusual; you won't

find the Einsteinian folds in any of the usual books of brain pictures.

Often national boundaries follow river valleys or mountain ridges, but not

always. So, too, with the brain's functional boundaries. Usually the ridge on

the back side of the central sulcus "valley" is a map of the skin's

sensations (the "sensory strip"), while the ridge on the front side

has a map of the muscles. Sensation and movement are thus separated by a

prominent valley - yet neurosurgeons see exceptions all the time, getting

sensory reports from some awake patients when electrically stimulating a short

way into frontal lobe.

The area in back of the face-and fingers part of the sensory strip has the

reputation of being important for spatial matters, such as finding your car in

the parking garage. It may be perhaps 15 percent wider than usual in Einstein.

What can we conclude from that? Only that it would be a good idea to

investigate living, functioning brains with the usual imaging devices, trying

to find other examples of the Einsteinian folds and seeing how those people

differ in functions we can measure: intelligence, creativity, verbal and

spatial skills. Or perhaps we might study people who love to create elaborate

spatial puzzles in their heads, like the cognitive scientist Douglas

Hofstadter, and see if they have unusual folds in this "inferior parietal

region."

We still tend, following Gall's phrenology, to give functional names, as if

an area were exclusively concerned with the named function. That may be almost

true in "visual" cortex, but most areas are multifunctional in the

manner of curb cuts (wheelchair use may be what paid for them, but bicycles,

suitcases, grocery carts, and skateboards now use them too). We usually

discover one function that compels our attention - and name the area after it!

And so onward to the reification fallacy. (It has a name, therefore it must be

a thing - and therefore other things must be in other places!)

Experts contemplating Einstein's brain can avoid that classic mistake

somewhat better than the student, but we still can't explain what the

Einsteinian folds really mean. We know all too well that there are lots of

variations between brains, every bit as extensive as the differences in

peoples' faces, and we know rather little about what it implies for enhanced

or impaired abilities. For example, the visual cortex at the back of the brain

is three times larger in some people than in others. Do they have finer acuity

or better color discrimination? No one knows yet.

It may be that sheer size isn't the main thing. Though there is some minor

tendency for IQ to increase with brain size, there are geniuses at both ends

of the size range (overall, Einstein's brain is about ten percent below the

male mean, even when corrected for age).

You can't help but wonder whether big brains, or oversized regions within

average-sized brains, aren't misleading us. Bigger is often better when it

comes to computers, but human brains overlap so many memories that what's

important is sorting them out. We grasp at sheer size because it is easy to

measure, but what we would really like to know is how swift, how sure, how

creative is this brain.

Einstein, after all, wasn't really in the calculation or deduction

business: he had to imagine a possible explanation for how some part of the

physical world worked, and then improve its fit with reality. So let us come

at Einstein from a different angle, asking about how brains implement

intelligence and creativity.

Those three pillars of animal intelligence - association, imitation, and

insight - are impressive but Jean Piaget said (and I paraphrase) that

intelligence is what you use when you don't know what to do, when neither

innateness nor learning has prepared you for the particular situation. While

we often use the term 'intelligence' to encompass both a broad range of

abilities and the efficiency with which they're enacted, it also implies

flexibility and creativity, an "ability to slip the bonds of instinct and

generate novel solutions to problems." In short, intelligence is

improvisational.

Just as a house is not merely a heap of construction materials, so it is

structuring which makes human mental abilities so different from those of the

apes. The higher intellectual functions include:

• Syntax, where the nesting of phrases and clauses are used to

disambiguate sentences longer than a few words, such as "I think I saw

him leave to go home," which has nested embedding involving four verbs.

• Planning, those speculative structured arrangements, such as

"Maybe we can go to the country this weekend if I get my work finished,

but if I have to work Saturday, then maybe we can go to a movie on Sunday

instead."

• Chains of logic, our prized rationality. But the emphasis

here is on novel chains, not routine ones. The most mindless of behaviors

may be segued, the completion of one calling forth the next: courtship

behavior may be followed by intricate nest building, then a segue into egg

laying, then incubation, then the stereotyped parental behaviors.

• Games with arbitrary rules, such as hopscotch. (And little

girls love to invent new rules as they go.)

• Music of a structured sort, such as harmony and

counterpunctual themes.

• Our fascination with discovering patterns hidden inside other

patterns, whether when listening to music or doing puzzles or laughing

at the punch line. Most people enjoy this search for the hidden pattern, but

scientists revel in it.

There's another kind of structuring, too, though it seems to have played

little role so far in our modern concepts of intelligence. You have to find

the right level at which to address a problem, neither too literal nor too

abstract. What's a level?

As an example of four levels, fleece is organized into yarn,

which is woven into cloth, which can be arranged into clothing.

Each of these levels of organization is transiently stable, with ratchet-like

mechanisms that prevent backsliding: fabrics are woven, to prevent their

disorganization into so much yarn; yarn is spun, to keep it from backsliding

into fleece.

We see the pyramiding of levels as babies encounter the patterns of the

world around them. They first pick up the short sound units of speech

(phonemes), then the patterns of them called words, then the patterns within

strings of words we call syntax, then the patterns of minutes-long strings of

sentences called narratives (whereupon she will start expecting a proper

ending for her bedtime story).

By the time she encounters the opening lines of James Joyce's Ulysses,

she will need to imagine several levels at once:

"Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came

from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor

lay crossed. A yellow dressinggown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind

him by the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned: Introibo ad

altare Dei."

There's the level of the physical setting (piecing together an old Martello

gun tower overlooking Dublin Bay with a full of himself medical student about

to shave). But there's also the more abstract level of metaphor. (Ceremonial

words and a deliberate pace - but ungirdled gown and an offering of lather?)

So much of our intellectual task, not just in reading Joyce but in

interpreting everyday conversation, is to locate appropriate levels of meaning

between the concreteness of objects and the various levels of category,

relationships, and metaphor.

To spend more time at the more abstract levels in an intellectual house of

cards, the prior ones have to be sufficiently shored up to prevent

backsliding. Einstein was probably pretty good at that. So are poets. But for

a theoretician such as Einstein, it was always a matter of comparing an

abstract level with a more concrete one.

I especially like Horace Barlow's 1987 suggestion that intelligence is all

about making a guess that discovers some new underlying order. "Guessing

well" neatly covers a lot of ground relevant to higher intellectual

functions: finding the solution of a problem or the logic of an argument,

happening upon an appropriate analogy, creating a pleasing harmony or witty

reply, or guessing what's likely to happen next.

It's a search for coherence, for combinations that "hang

together" particularly well. Sometimes this provides an emergent

property: the committee can do something that all the separate parts couldn't.

It can be like adding a capstone to an arch, which permits the other stones to

support themselves without scaffolding - as a committee, they can defy

gravity.

Creativity and intelligence share features, but we all have intelligent

friends who are not especially creative, and vice versa. To be creative you

must be able to build that house of cards to higher and higher levels,

constantly seeking quality. Scientists learn to cherish their mistakes rather

than suppressing them, using them to illuminate the problem. You have to avoid

throwing out the mediocre too soon, instead trying variations in search of a

better fit.

But there's no little person inside the head to stack up the house of

cards, so what self-organizes a higher level? In the simpler physical systems,

noise (as in diffusion) can provide the raw material for self-organizing

structures (such as crystals). As Jacob Bronowski observed: "The stable

units that compose one level or stratum are the raw material for random

encounters which produce higher configurations, some of which will chance to

be stable."

If there is an organizational principle in the universe that is even more

elementary than Darwin's, it is Bronowski's. What Darwin discovered, however,

is the principle that allows the quality of each level to be automatically

improved. Rather than just crystals, you get a recursive bootstrapping of

quality fits, for improving how well things hang together. There's an

algorithm for doing this coherence improvement which we can see in species

evolution and, on the time scale of mere weeks, when so-so antibodies are

improved during the immune response into good fits to the invaders. And the

brain apparently (see my book, The Cerebral Code) has the right

circuitry to operate the same Darwinian process on the time scale of thought

and action, as we contemplate what to say next. We can start with incoherent

parts, such as that jumble of people, places, and events of our nighttime

dreams, and make a better story out of it, judging it against the real world

or our memories of it.

We all know people of many talents who, because they lack one crucial

talent, are largely ineffective. Einstein was surely running on all cylinders.

He needed, for example, that frontal-lobe ability to maintain agendas and

monitor progress. His parietal-lobe spatial abilities gave us stories of light

beams bending around the sun, or trains approaching the speed of light. He

surely was able to build his mental house of cards to magnificent heights,

while always comparing it to the real world, judging whether it provided a

good fit.

There was a symphony playing once in that oddly-folded brain of Einstein's,

and it achieved a wonderful coherence with what goes on in the rest of the

universe.

___________

William H. Calvin is the author of The

Cerebral Code (MIT Press 1996) and, together with the linguist Derek

Bickerton, Lingua ex Machina: Reconciling Darwin and

Chomsky with the Human Brain (MIT Press 2000). He is a theoretical

neurophysiologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, with a web page

at http://WilliamCalvin.com.

For further reading:

Jean-Pierre Changeux, L'Homme Neuronal (Fayard, 1983)

Mark Turner, The Literary Mind (Oxford University Press, 1996)

Daniel C. Dennett, Kinds of Minds (Basic Books, 1996).

William H. Calvin and George A. Ojemann, Conversations

with Neil's Brain (Addison-Wesley, 1994).

Antonio R. Damasio, The Feeling of What Happens

(Harcourt Brace, 1999).